Audition: Original organ (AJ Gordon 2x) - a capella (harmonic sketch) - descant with harmonization

1 Unison

My Jesus, I love Thee, I know Thou art mine;

For Thee all the follies of sin I resign;

My gracious Redeemer, my Savior art Thou,

If ever I loved Thee, my Jesus, ’tis now.

2. Organ, SATB canonical harmonization

I love Thee, because Thou hast first loved me,

And purchased my pardon on Calvary’s tree;

I love Thee for wearing the thorns on Thy brow;

If ever I loved Thee, my Jesus, ’tis now.

3 a cappella, sketch harmonization

I’ll love Thee in life, I will love Thee in death,

And praise Thee as long as Thou lendest me breath;

And say when the death-dew lies cold on my brow,

If ever I loved Thee, my Jesus, ’tis now.

4. descant

In mansions of glory and endless delight

I’ll ever adore Thee in heaven so bright;

I’ll sing with the glittering crown on my brow,

If ever I loved Thee, my Jesus, ’tis now.

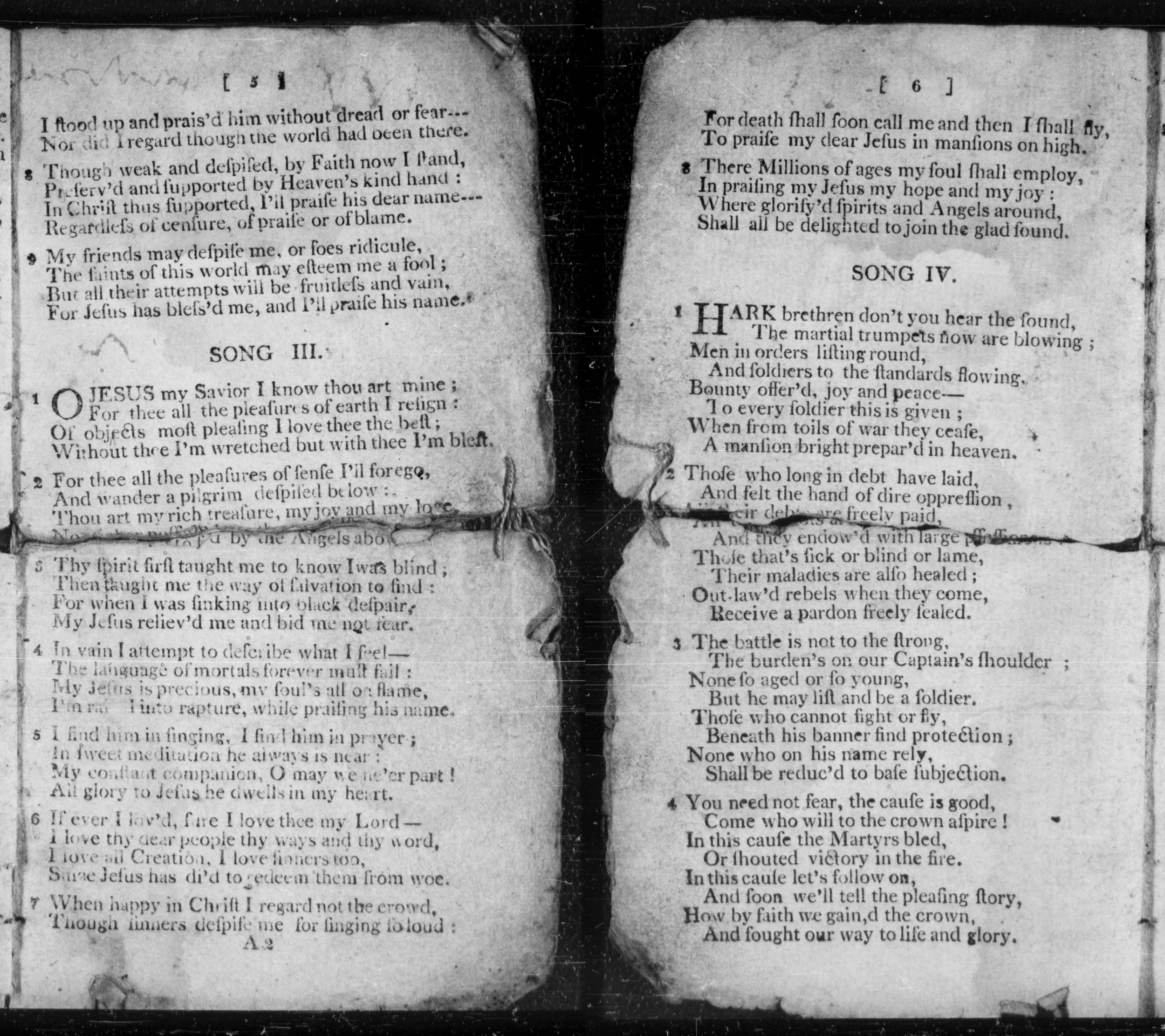

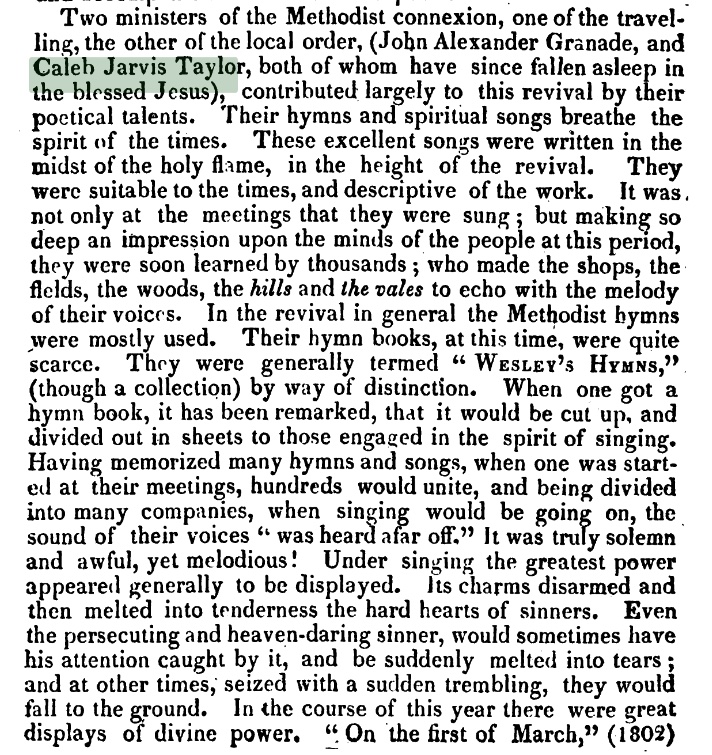

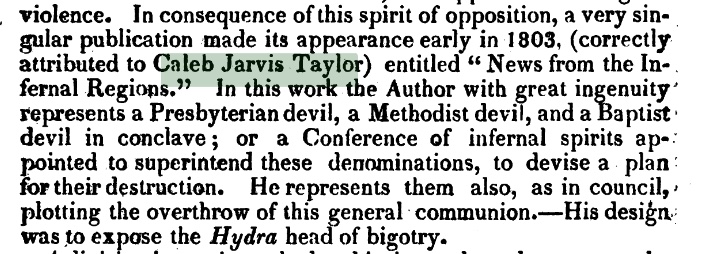

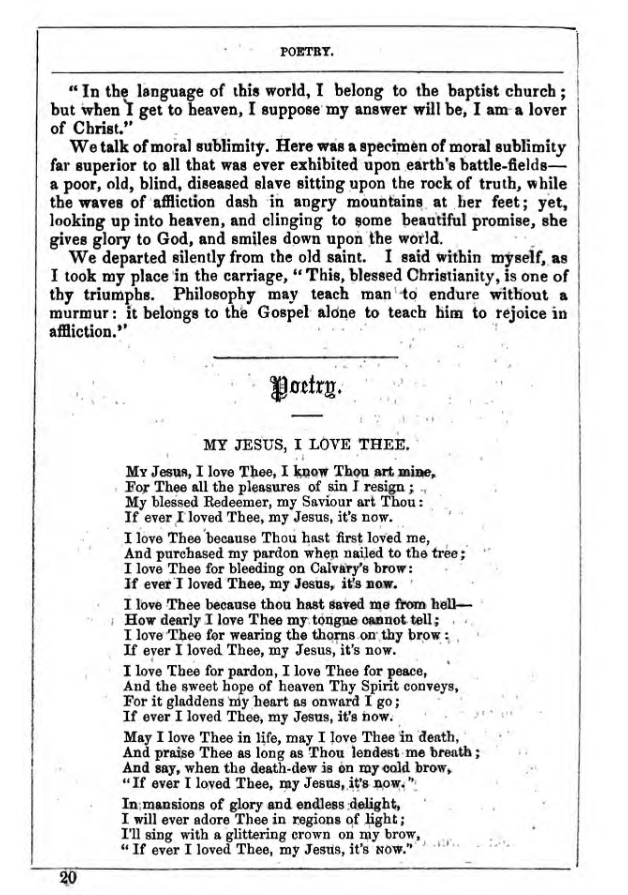

We have been told a sweet story about how this hymn came to be. If only it were true. “My Jesus I love thee, I know thou art mine” was published with the verses we sing today by William Antliff in 1862, a composite of unattributed source material. One source is known, however: "O Jesus, my Savior, I know thou art mine" (Caleb Jarvis Taylor, 1804) contributes a significant portion of the language imported by Antliff with other material to produce this hymn. It is not the work of a child, under Antliff it appears to be a work for a child. It was the fifth imprint, The London Hymn Book that realized its greater possibilities as a hymn for any child of faith, no matter their age.

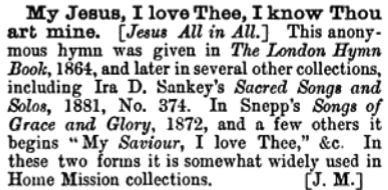

In early 1862 this English derivative first appeared with the incipit “My Jesus, I love thee, I know thou art mine", developed over five printings, in every instance without attribution (click dates to see reference images in a popover; links to sources in the footnotes):

- 1862 ed. Joseph Foulkes Winks in The Christian Pioneer, a theological journal, in six stanzas, evincing a work-in-progress.

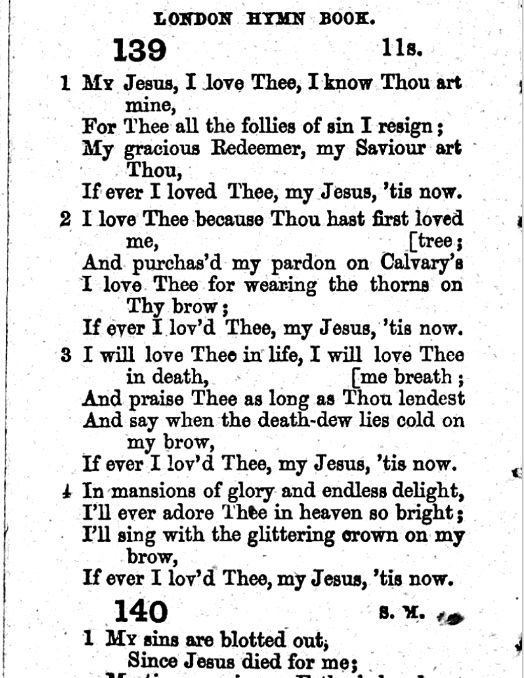

- 1862 / 64 / 65 ed. William Antliff in the four stanzas as we have them today, first in October of that same year in The Primitive Methodist Magazine, then twice more - explicitly for a young audience.

- 1864 or poss. 65 ed. Charles Russell Hurditch in The London Hymn Book (non-denominational, compiled for a general audience) which changed two words.

Antliff's re-engineering cast duller material into a luminous alloy. Extraneous verbiage from the earlier printing was smelted away, small but precise substitutions refine the lexical flow, and the focus was concentrated on the imagery of the thorns, the death dew, the glittering crown 'on my brow' to lend the hymn palpable immediacy – past, present, and future, "my Jesus, it is now".

The lack of proper attribution - a misfeasance Antliff concedes - leaves a vacuum filled by a mythattribution with factual documentary errors to a schoolboy named William Featherston, who allegedly submitted a hymn to either an obscure English theological journal, or a denomination excommunicated by his own and which had no presence in the colony of lower Canada where he lived; it would be another four decades before this legend emerges. Oh, the ironworker, James Duffell? His name did not appear until two decades after that. Evidence for either anecdote is entirely absent. Moreover, much of the hymn's language is unmistakably Taylor's in a proportion that categorically excludes attribution to any single author. Continued ambiguity over a did-he-or-didn't-he mystery is the oxygen-rich atmosphere that keeps these fictions alive.

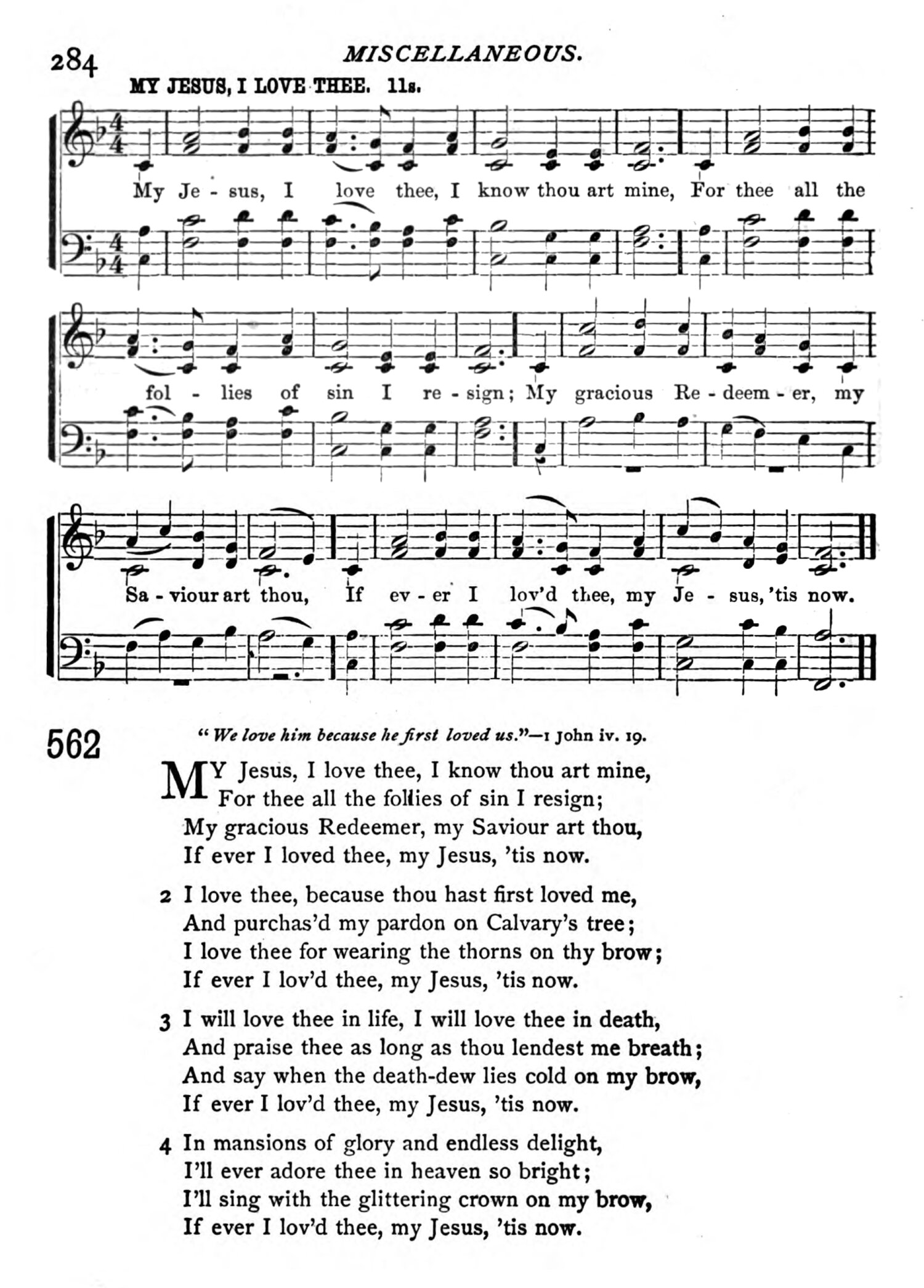

The tune / In spite of, or perhaps because of, these machinations, the hymn's theology acquired a keen evangelical edge, needing only a tune sufficient to make its message compelling. Several tunes were tried along the way, but the one that landed was composed by Adoniram Judson Gordon, pastor of Clarendon Street Baptist Church in Boston and founder of the college now named, like the tune, after him. GORDON first appeared in The Vestry Hymn and Tune Book (Boston, 1872), a volume he edited with the same versification found in The London Hymn Book, published eight years earlier.

© David Maurand. Commentary CC BY-SA 4.0.

May 25, 2025 (rev. June 12, 2012)

The above has been reviewed by Carl P. Daw, Jr., Curator of Hymnological Collections, Boston University School of Theology Library. Special acknowledgment to Chris Fenner, Digitial Archivist at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and Managing Editor of the Hymnology Archive for important corrections...the details matter.

Further observations click below to open

The Primitive Methodists are the connection between the two variants. Taylor wrote for the Amerrican camp meeting movement which sired a denomination in England known as the Primitive ("first order") Methodists. Published originally in the form of a songster (pamphlet) entitled Spiritual Songs, "O Jesus, my Savior, I know thou art mine" was soon reprinted in other publications, widely used in both American camp meetings and in the similar movement they inspired in England. When expelled by the Wesleyans over camp meetings, the Primitive Methodists incorporated separately.

The phenomenon of the American rural open air camp meeting was  introduced to England in 1805 by American itinerant preacher Lorenzo Dow, who proved wildly popular; two years after landfall and subsequent evangelizing, camp meetings commenced in England and caught on immediately. This occasioned a division among Methodists. Wesleyan congregations refused to admit the supposed rabble of open air converts to their now mature Wesleyan churches, which were ironically founded in just such a movement - prominently and literally a foundry.

introduced to England in 1805 by American itinerant preacher Lorenzo Dow, who proved wildly popular; two years after landfall and subsequent evangelizing, camp meetings commenced in England and caught on immediately. This occasioned a division among Methodists. Wesleyan congregations refused to admit the supposed rabble of open air converts to their now mature Wesleyan churches, which were ironically founded in just such a movement - prominently and literally a foundry.

After four years of unsanctioned camp meetings, the Primitive Methodists separated (1811) and established itinerant preaching circuits of their own and a single transatlantic mission emerged. As the industrial revolution gathered steam, emigrés from England had begun working in American mines and factories, their spiritual needs attended by missionaries from home. An 1819 account two years posthumously of Taylor's contributions to hymn singing noted that it was common for pages to be torn out of the songsters and carried as separate sheets (passage in image below), which might explain one way the hymn might have arrived in England - in the pockets of returning missionaries. It is also entirely possible that Lorenzo Dow, who was known to have brought literature with him, brought along copies of Taylor's Spiritual Songs in his 1805-1807 visit, or included it in his own camp meeting hymnal.

Caleb Jarvis Taylor was born 1763 into a Roman Catholic family in Maryland, converted at age 20, and a few years later founded Mount Gilead Methodist Church in what was then a frontier state, the Commonwealth of Kentucky...in Bourbon County, now famed for its whiskey. He is the author of several hymns (Hymnary.org lists 26), many still sung today, including the original. He was highly regarded both as preacher and hymnwriter by the English, and his original version was documented as circulating in England during the period of joint organization. Forty-two years after his death, an 1859 article on the camp meeting songwriters devoted several pages to his biography, noting particularly his poetic contribution.

Winks and Antliff, the publishers who separately produced the 1862 versions with the new incipit, were in friendly competition contemporaneously - not only with their denominational flagship magazines, but with related children's' editions, though the longer version in Winks was for an Arminian journal instead, a theological position consonant with Methodists. Since neither provided attribution, we can't be sure that one or the other didn't write both of them, or whether there is a synoptic Q version yet undiscovered supplying some proportion of the hymn not written by Taylor. Though both editors published a great deal of poetry, it can't be said that either was recognized as a poet; however, Antliff to that point had been actively editing poetry and prose, and later a biography of Lorenzo Dow. In his foreword to The Village and Other Poems (James Dodd, 1853), Antliff, the book's editor, wrote "Any boy may string words together so as to make a tinkling, jingling, sound ; but your true poet will not find this meet his taste ; he will ask for feeling, sentiment, real living poetic heat." This tells you how he would have regarded a one-and-done submission.

The earlier Winks printing has the feel of a work in progress, the hymn under Antliff's editorship is a finished piece - it is polished, has a clear theological cadence, and matches the version we sing today. Both shared a deep interest in children's literature, and struggled deeply to explain to a young audience why children die. It is reasonable to conclude the work was intended from the outset for a young audience - this, at least, is how Antliff positioned the work in his two subsequent printings. This might explain the hymn's final reduction to the purely familiar voice, which lends a sense of hope and immediacy.

With the addition of the young Hurditch to late-career Winks and mid-career Antliff, the evolution of this hymn involved a trio of professional communicators with shared commitments to theological, educational, literary, pedagogical and organizational objectives. In the midst of significant changes in copyright laws, they managed budgets and networks of printers, binders, typographers, and engravers. They were preachers, they founded schools, they led entire organizations - these were talented and enterprising creators. This is how organizational editing is done.

This circuitous process may not be either miracle story we've been told, but it is nonetheless a miracle, not only because we possess such a hymn, but that such a shimmering hymn possesses us.

The authoritative The Dictionary of Hymnology listed "My Jesus I love thee" as anonymous in 1902, but explicitly documented the connection between the Taylor's original and Antliff's unsigned version (see the inset image above). A scan of numerous hymnals through 1909 credits the source as The London Hymn Book exclusively, though in our view, this attribution really belongs to The Primitive Methodist Magazine, or more particularly its editor William Antliff, who published the hymn three times between 1862 and 1864 with 98.6% of our current versification. The London Hymn Book of 1864 makes a final revision of only two words.

Thus, our colophon reads:

Text: composite, ed. William Antliff (1862), after Caleb Jarvis Taylor (1804) and others s.n. | Music: Adoniram Judson Gordon, 1872

© David Maurand. This additional commentary CC BY-SA 4.0

May 25, 2025

This is not the first hymn or tune giftwrapped in a completely fictitious backstory, fabricated to give the work an aura of otherworldly origin to improve public acceptance. We have debunked a couple others on this site, notably ST. JOAN and GARDINER (which you may know as Germany or Beethoven). The hymn Abide with me likewise has two mutually exclusive origin myths created by the hymn's own writer, Henry Francis Lyte.

This all-too-common ploy may, in this instance, have a Boston connection involving one of A.J. Gordon's music directors.

In 1876, after two years as music director at Gordon's Clarendon Street Baptist Church, George Coles Stebbins - a prolific hymn writer - left to take up the position at the Baptist church a mile away now known as Tremont Temple. There he teamed up with with Dwight Moody and singer Ira Sankey, no strangers to self-promotion; this trio traveled extensively together. All contemporaneous attributions were to "A.J. Gordon, by per[mission]".

To complete the cycle of contempt for authenticity and authorial integrity, in 1906, this story appeared (with significant factual errors) in a memoir by Ira David Sankey, My Life and Sacred Songs (London: Morgan & Scott, 1906) - but only in the British edition; the American version (Philadelphia : Sunday School Times Co.1906) completely omits the story, with an attribution to 'anonymous'; the same with the expanded 1907 edition. It leaves open the question as to whether this signals editorial mischief undertaken in England. Except for the one outlier publication, Sankey's name is never connected to anyone except Anonymous, including a number of hymnals co-edited with Stebbins. Blinded (or nearly so) by glaucoma, and only months from his death, one might ask if Sankey ever knew of this version.

And thus the myth has become part and parcel of the hymn itself while the true creators have been forgotten. Even A.J. Gordon didn't pretend to know where this hymn came from.

David Maurand CC BY-SA 4.0

May 25, 2025 rev June 12 2025

FURTHER READING

REFERENCE IMAGES

click image to enlarge

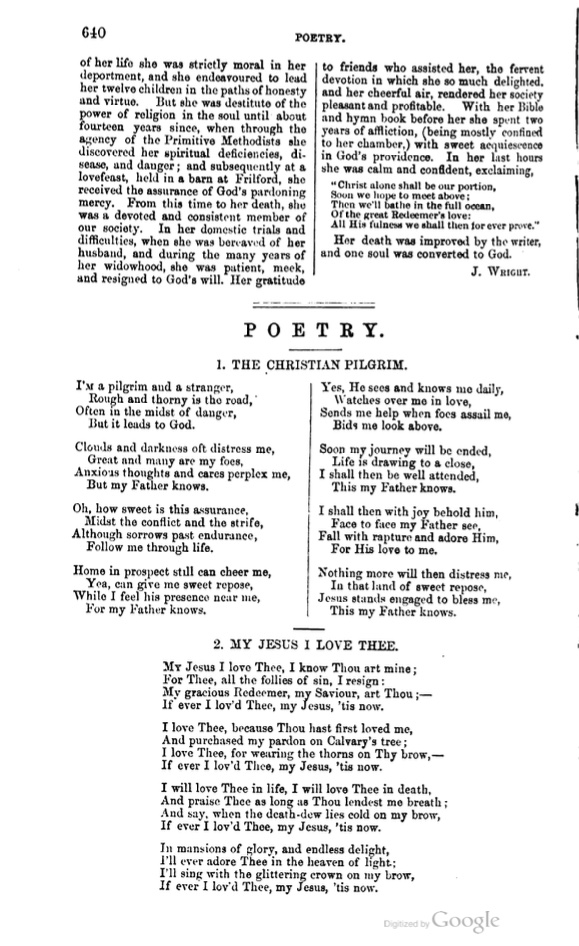

The Christian Pioneer, 1862 Vol XVI no.2, Ed. Joseph Foulkes Winks, Bodleian Library CC-BY-SA

Six verses

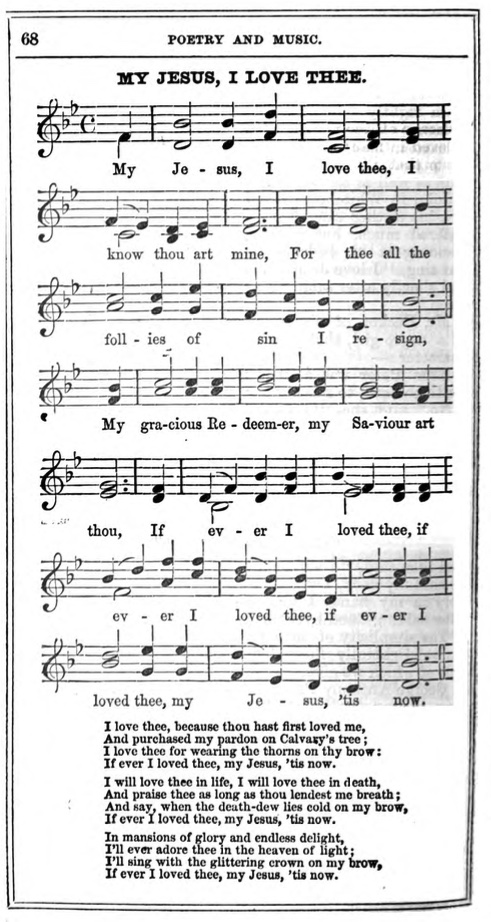

The Primitive Methodist Magazine, Oct 1862, Ed. William Antliff, Bodleian Library CC-BY-SA

Reduced to four verses

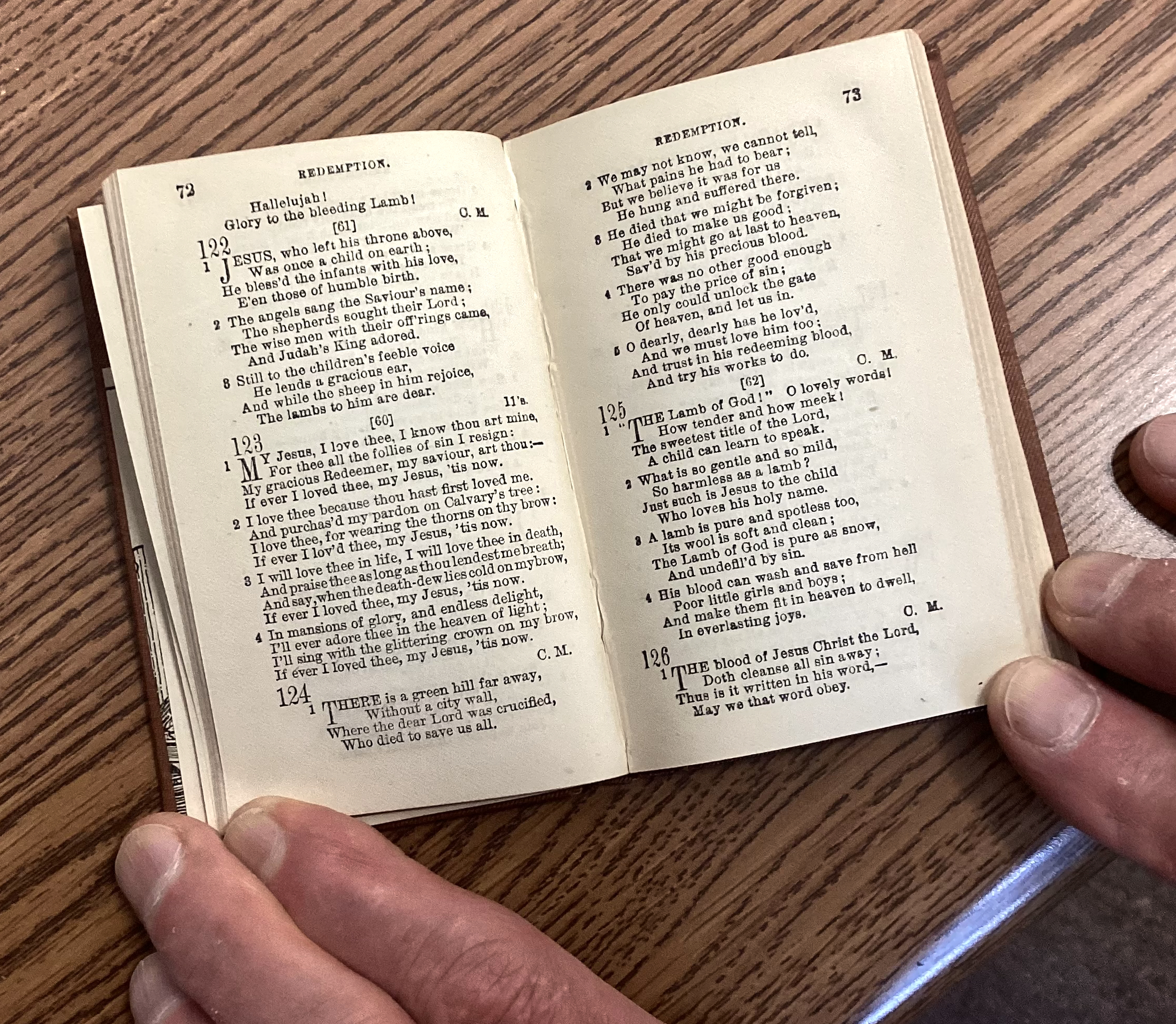

The Primitive Methodist Sabbath School Hymn Book, Ed. William Antliff, School of Theology Library, Boston University CC BY-SA